Iron Curtain, Iron Corridor… Iron Canvas

How much complicity do we share in the Russian-Ukrainian War? We knew that an authoritarian kleptocrat (with nuclear weapons) who has been in power since 1999 recently started increasing his saber-rattling to overcome his own waning popularity, and then piloted a ramshackle, redlining, petrol-fueled state down Fury Road straight toward disaster in Ukraine. Over the last decade we watched the Russian trolls meddle in elections, weathered cyberattacks and were blindsided by the Belarus migrant crisis, marveled at the Wagner group’s Us-like version of Blackwater, shook our head at the evident corruption in Sochi, and quietly grieved the persecution of journalists and LGBTQ in Russia from afar. Now, we’re not surprised by both the invasion of Ukraine and the unfolding tragedy. How much are we responsible? 1%? ½%? 1/10 of 1/10 of 1/10 of 1%?

We didn’t pull the trigger, but in the bazaar of realpolitik did we sell the thug the gun? The ammunition? Did we even consider a background check?

We didn’t run the drunk off the road, but were we the bartender? Did we hand him his keys? Were we a passerby in the parking lot watching him stumble to his car?

Putin on Fury Road (over our objections)

Concept by Gary, Artwork by Luyzk

We live in the world together, we share the ecosystem, economic systems and geopolitical systems with Russia, among many others, whether we like it or not. We know that the Security Council system is broken. We know that drastic action is needed to address climate change. We know the world is driven toward these precipices by corruption and greed, yet we do little to regulate our financial systems that perpetuate offshore flows and dirty money. These aren’t easy problems in the Muddle. indeed, in many ways it is hard to see how truly bad the tragedy of the commons is because all of the sheep are in the way.

In the Tragedy of the Commons, all the sheep say: Sieze the Hay!

Concept by Gary, Artwork by Luyzk

Yet, if we’re ever going to get to a sustainable peace, in which people work together to solve the collective problems that are stacking up, we’re going to have to, someday, stop using our national interests as excuses for continuing to contribute to our shared tragedies. This might very well be science fiction – a world in which humanity works together for common cause, peace and prosperity – but many believe it is possible. It may not (probably won’t) happen in our lifetimes. But happen it must if we’re ever to find a smooth path to a sustainable peace (there are many rough paths to other types of peace). How do we do that? Blattman channeling Kahneman says we need to think slow - let’s (re-)consider the rush to rebuild the Iron Curtain:

During the cold war, the Iron Curtain was the metaphorical wall between the USSR and the West, restricting the movement of trade, people and ideas, though every system is porous and all three still managed to seep through the border. Today, there are calls to rebuild the Iron Curtain – indeed, the many sanctions against Russia, the freezing of assets and the flight of the intelligentsia are the beginning of at least an “Iron Veil” being pulled. As the Ruble continues to falter and the Russian economy collapses (again), the autarky of Russia will continue to become isolated. Incereasingly, those connected to Russia economically and culturally are cutting ties. Even if the sanctions were lifted tomorrow, the international isolation would continue, further perpetuated by perceptions of corruption and graft in the Russian system. An Iron Curtain is being rebuilt.

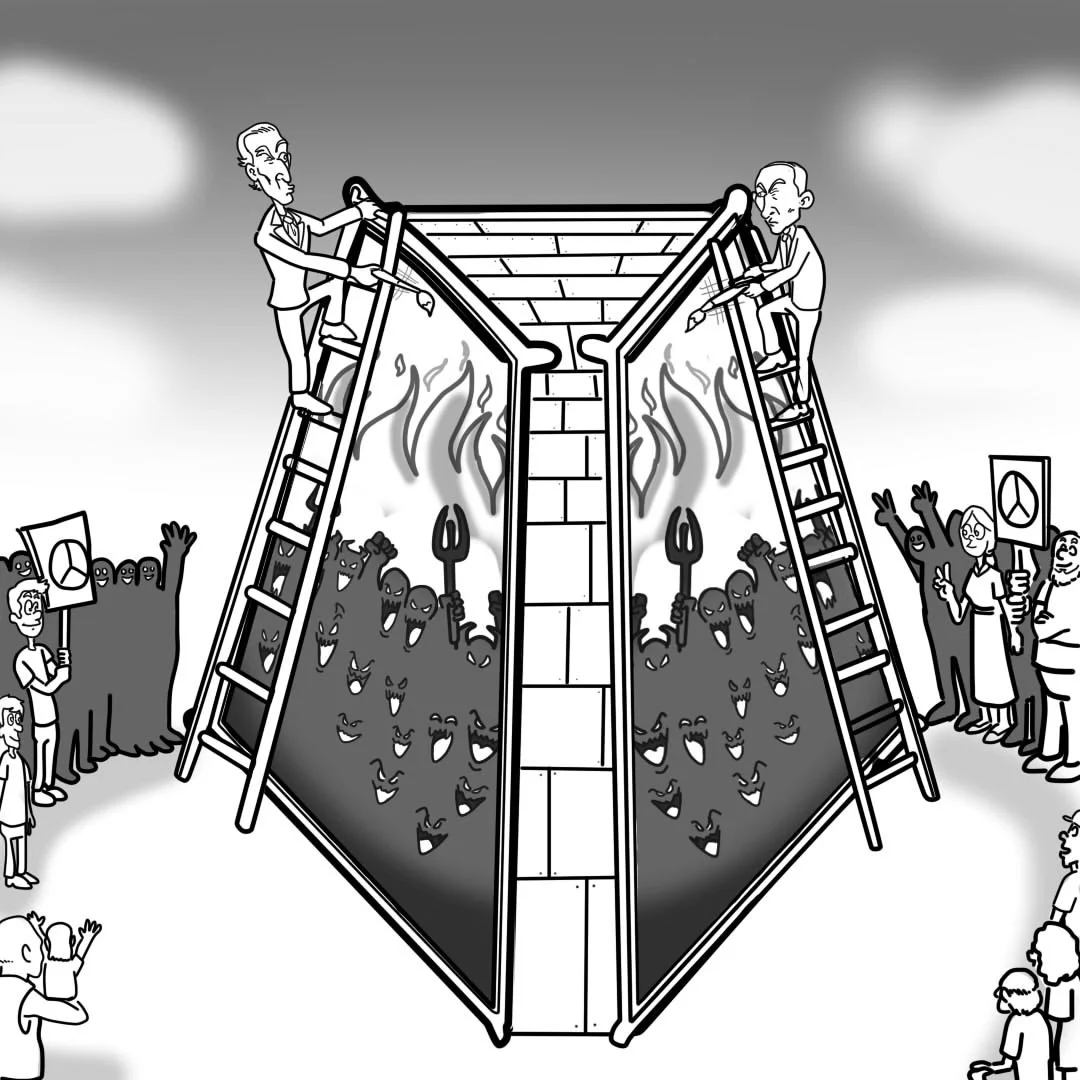

It is important to understand that the curtain is useful to leaders on either side of the curtain, and, so, leaders on both sides are contributing to it. For example, Putin often uses narratives about Russian isolation (it is us against the world) that resonate with many of his supporters. Actions that further isolate Russians from the rest of the world support this narrative and consolidate support for Putin, not just with nationalists, but with both oligarchs and the poor and other Russians who find themselves with no other options. Additionally, with control of the media and diminished access to the outside world, Putin is able to control narratives – he is effectively the only one that can “see” over the curtain and report back to his people on what the West is doing on the other side, reinforcing the narratives he is building. Meanwhile, the other side (The West) benefits whenever they can rally around “anti-Russian” sentiment. Institutions, like NATO, need a raison d’etre and a rationale like this perpetuates them. Initial conversations of a “Marshall Plan for Ukraine” have two meanings: i) they can rally resources for development for Ukraine and, ii) because of the values ascribed to the Marshall plan during the Cold War - they can reinforce the isolation of Russia. Russia, was, after all, the biggest loser from the Marshall Plan, and actively tried to sabotage it, as it eventually become the mechanism for the West building a powerful economic system that would outstrip Soviet growth. Sanctions regimes, transfers of weapons systems from NATO allies, a new Marshall Plan - all evoke the Cold War (for better or worse) and buttress a new Iron Curtain - being built by both sides.

Leaders benefit from perpetuating false choices

Concept by Gary, Artwork by Luyzk

We’ve been here before and it didn’t end well. Is the plan to encircle Russia with a new Iron Curtain, inclduing a new Marshall Plan and continue expansion of NATO and wait for the next cornered autocrat (Putin or the next Putin) to lash out? Reviewing Op-Eds from 1993 or 1999 show just how much things stay the same, no matter how much they change. An alternative is to learn from history and start to address the systemic and root causes of these conflicts. A new narrative that would break the cycle would still need to draw on the root narratives prevailing in the region. For example, an “Iron Corridor”, could acknowledge that isolation is not a solution, that people, goods and ideas need to be able to move for development to happen and that a special economic zone could benefit both Ukrainians and Russians to promote economic growth, serving as a model for other Russian enclaves. An investment in joint customs and border patrol could also provide an entry point into better governance, starting the conversation of addressing Russia’s rampant corruption. These are just some of the many solutions that might straddle an Iron Corridor.

An Iron Corrridor may not be the solution, but it is one of many to consider. Indeed, policymakers who want to genuinely solve these problems and move forward into a new (and sustainable) peace, need to re-imagine the “Iron Canvas” before them – or risk revisiting this nightmare again in 20 years.

If we don’t, how much will we be responsible then?

Read more about how leaders use polarization and false choices to limit our solution space and how Scrumble can be used to open that space up.